FIVE years after Western air power helped remove Muammar Qaddafi, the chances of another intervention in Libya are steadily increasing. Islamic State may be retreating in Iraq and under pressure in Syria, but in Libya it is a growing menace. At a meeting in Rome on February 2nd of the international coalition against Islamic State (IS), Libya was high on the agenda.

That followed talks in Paris on January 22nd in which General Joe Dunford, the chairman of America’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, agreed with his French opposite number that they were “looking to take decisive military action” against IS in Libya.

It has since been confirmed that American and British special forces are already on the ground there in small numbers, making contact with local militias.

Unsurprisingly, the same conditions that have made Libya such fertile territory for IS are also making it hard to plan an intervention that would have a good chance of success.

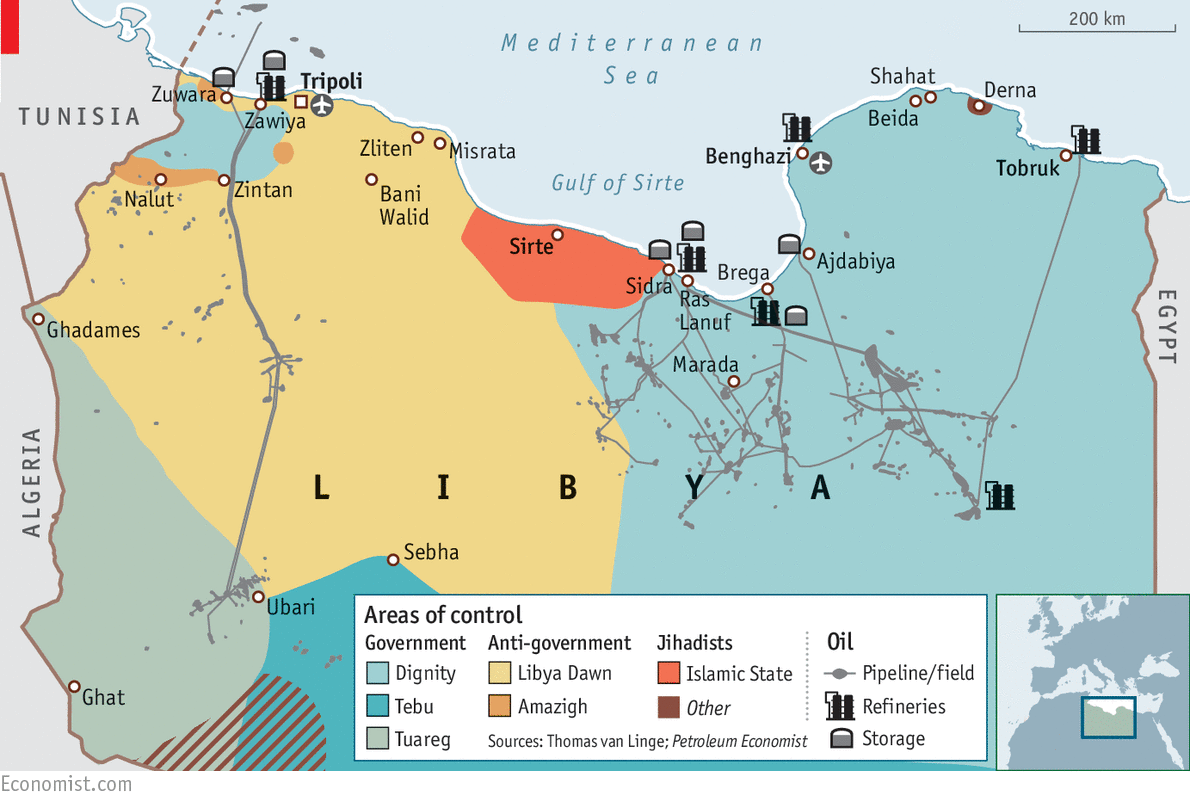

The spread of IS has been helped by a 20-month-long civil war in which it has been happy to attack both sides. In the west it faces Operation Dawn, a cobbled-together alliance of Misratan, Berber, Islamist, and other militias that back the so-called National Salvation Government in Tripoli. In the east it faces Operation Dignity, an equally loose-knit coalition of militias and regular military forces that includes some former regime supporters.

Operation Dignity is led by General Khalifa Haftar, who backs a rival parliament, the internationally recognised House of Representatives, which is based in the eastern city of Tobruk.

It has not all been plain sailing for IS. It suffered a setback in mid-2015 when its attempt to take over the eastern town of Derna met resistance from local tribes, repelled by its brutality, and rival Islamist militias.

But since absorbing the most militant members of a powerful local jihadist group, Ansar al-Sharia, it has succeeded in establishing an area of control spreading out about 100 miles (160 km) on either side of Sirte, Qaddafi’s old coastal stronghold, which sits between Tripoli and Benghazi.

From Sirte, now described as the new Raqqa (IS’s capital in Syria), IS is expanding east and attacking oil installations at Sidra and Ras Lanuf.

The militia-based Petroleum Facilities Guard, although hugely outnumbering the 5,000 or so IS fighters in the area (the UN estimates 3,000, which may be on the low side), appears unable or unwilling to prevent IS from doing further damage to an industry that has seen output fall to less than a quarter of the 1.6m barrels a day being pumped in 2011.

The mounting concerns about IS in Libya have spurred diplomatic efforts to end the civil war through the creation of a government of “national accord”. Hopes were raised by a peace deal brokered by the UN that was signed in Morocco on December 17th by delegates from the rival parliaments. Lacking broad support, the agreement was premature.

Both assemblies insisted that the signatories represented only themselves. Nevertheless, the UN appointed a presidential council, which in turn named a new government under prime minister Fayez Sarraj, a member of the Tripoli-based parliament, that is now waiting in a hotel in Tunis.

On January 25th the parliament in Tobruk rejected the proposed government, while affirming the peace plan, if changes were made. The most important demand is for the removal of Article 8 of the agreement, a provision that would give the presidential council the right to appoint the heads of the armed forces and the security services.

That would threaten the position of General Haftar, who harbours ambitions to be Libya’s next strongman. Supported by outside powers, including Egypt, General Haftar still holds much sway in the east, where his forces have cracked down on dissent. But he has a growing number of critics.

Deal or no deal

The UN has said that it will not reopen the deal. The parliament in Tripoli has not voted, but its prime minister, Khalifa al-Ghawi, has threatened to arrest the new government’s guards if they enter western territory.

It does not help that Tripoli is also the location of the Libyan state’s only functioning institutions: the national bank, the state oil firm and the sovereign wealth fund. “The entire plan is looking pretty forlorn and anaemic,” says Frederic Wehrey of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think-tank.

Divisions within the army may ultimately undermine General Haftar in the east. He is already despised in the west, where he is seen as a scourge of the Islamists.

But for now Libya is no closer to a unified command that could bring together its various combatants and ally with Western powers to fight IS.

Much of the public distrusts the UN, not least because its former envoy to Libya, Bernardino León, took a job with an official think-tank in the United Arab Emirates, which supports Mr Haftar, after stepping down last year. But they have also grown tired of the fighting. Nearly half the population needs humanitarian assistance, says the UN. Over 1m Libyans are thought to be suffering from malnutrition, and 500,000 have been forced from their homes.

Where does this leave the plans for a Western intervention against IS? In Rome John Kerry, America’s secretary of state, suggested that once the unity government is formed outside powers will respond to any request for military help, not least because they want to defeat IS.

That assumes, however, that the international pressure on the two parliaments in Tobruk and Tripoli is close to yielding a deal that sticks. But as Claudia Grazzini of the International Crisis Group says, Article 8 is the “cornerstone” of the agreement. Tobruk’s opposition to it, she says, means that all the other guarantees contained within it, such as consensual government based on a separation of powers, “just crumble”.

Meanwhile, by targeting oil and petroleum infrastructure, the jihadists of IS are trying to destroy any chance that anyone will be able to put the Libyan state back together.

The central bank has burned through much of its foreign reserves paying salaries and subsidies to both sides, while the Libyan Investment Authority’s funds remain frozen. If oil production falls even further, the humanitarian disaster will only get worse.

Nobody has any illusions that, on their own, Western air strikes can do more than contain IS. But Ms Grazzini says putting large foreign forces on the ground would be “unwise and risky”, and efforts to pick militias deemed worthy partners might just mean strengthening them in their battles against other local groups. Mr Wehrey agrees on the need to proceed carefully, but says that “we can’t wait” for a unity government to be “pushed over the line”.

He is more hopeful that special forces on the ground can work with local militias, such as the Misratans, who have repeatedly asked for military assistance from America as “co-ordinator, broker and referee”. Air strikes, he believes, can play an enabling role and disrupt IS operations. In a situation where there are no good options, doing nothing may be the worst.

Source: The Economist

UM– USEKE.RW